As we get closer to the American elections, and then moving into the Canadian elections next year, I find it more and more imperative that we work to effect a fundamental change in the way we interact with social media and, by extension, how we interact in real life. Over the last ten years or so my concern over the culture has grown from mild alarm at some people’s online behaviour, to something approaching real fear that we are at a tipping point into another real-world dark age, specifically with respect to intellectual and cultural decline. And violence.

It’s not all bleak though. Thanks to many private conversations, I know I am not alone in my concern, and I do see signs that there are public figures with a legitimate desire to change this trajectory, as opposed to leveraging the culture for their own personal gain. And considering the magnitude of people who, exclusively through social media, get their news, form their opinions, and – maybe most troubling – learn how to communicate, social media is where it has to start.

If we can do it, it won’t be through any kind of censorship or similar attempts to control how people use their favourite platform though. It has to be you and me. We have to change the nature of our posts. And so I had this idea of a filter, or sieve, that we can apply to our more meaningful posts to both increase their effectiveness, and also combat the culture that is propelling us toward a precipice.

Consider this. If you want to engage in political posts on social media, that is your choice, and I support it. Keep in mind though that these posts are, by nature, argumentative, in that political posts always argue for or against some candidate or issue. Which on its own is not a problem. Argument (or debate) is not a fight. The idea that arguing equals fighting is something that’s manifested because people like getting attention and scoring points. True argument is not a contest, but a means to pursue truth and, conducted properly, is how we progress. Because the acquisition of truth can never be considered a loss, proper arguments have no losers, and in that sense they have no winners either, because to win an argument someone would have to lose.

But many people argue poorly, because they argue for points.

In the philosophical study of argument there are many identified fallacies. If you’re not familiar with the idea of a logical fallacy, think of these as techniques or strategies that falsely trick you into thinking they are effective. When you employ them you or your audience may think you’re “winning” but you have not made a true case. To avoid this, and hopefully steer us away from the precipice, I ask that you apply what I’m calling an effectiveness sieve to your words before you click that post button.

Run your post through the following sieve. If you can’t answer yes to all three sieve questions, refine your thoughts until it passes them all, then go ahead and put it out there.

- Do my words avoid belittling, shaming, or otherwise personally attacking someone who doesn’t agree with my position?

- Does my post allow for (and even maybe invite) respectful discourse with someone who disagrees with it?

- Does my post offer information/education that someone who disagrees with me might not have considered?

You can actually stop reading here, if you like. The value of each question is probably self-explanatory. But if you want to dive a little deeper into the reasoning behind these criteria and their relationship to common fallacies, or to reflect a little more deeply on whether or not your own posts are effective, read on.

(A word of warning though: I use examples below to illustrate the points and a lot of them are, by design, inflammatory in concept and language. I am not expressing my views in any of them – I am parroting posts I have seen in my social media feeds.)

Sieve Question One

“Do my words avoid belittling, shaming, or otherwise personally attacking someone who doesn’t agree with my position?“

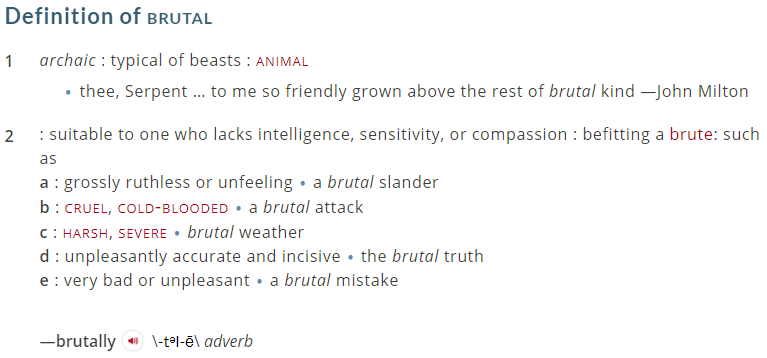

Fallacy This Helps Avoid: Ad Hominem (Attacking the person)

This occurs when instead of challenging an idea or position, you irrelevantly attack the person or some aspect of the person who is making the argument. The fallacious attack can also be aimed at a person’s membership in a group or institution.1

How to tell

Imagine that someone who holds an opposite position made a post worded like yours. Would you take it as a personal attack, or would you view it as someone simply supporting ideas that you disagree with? Keep in mind that we can challenge ideas without attacking the people who embrace them. In fact, this is the only way to dismantle dangerous ideologies. In democratic societies where change essentially requires consensus, attacking opponents instead of ideas is possibly the worst way to stimulate progress. Consider this example:

Example 1

“Considering the unbelievable depths of stupidity you display in believing that climate change is a hoax, it would obviously be a waste of time explaining the facts to your fascist republican ass.”

Example 2

“You have been duped by the lamestream media, so I will leave you to your weak-minded, sheeple liberal delusions about how solar power will ‘save the planet'”

Example 3

“I read conflicting views on whether climate change is real, if it is a concern, and if it is totally caused by human factors. I am not an expert, and it’s not always easy to filter out the real experts from the ones who claim to be. And even then, it’s not always easy to filter out which experts, if any, are twisting their analyses to suit some underlying agenda. However, the scientific consensus points at climate change being a real danger, and being attributable to human factors. The recommendations to address it seem to be a net good, even if the premise that we are the problem isn’t totally correct.”

It should be obvious what’s happening in the first two examples. There is no attempt to change anyone’s mind. It’s just mud-slinging peppered with tired insults engineered to pump up the audience members who agree. Neither post does anything to address the issue of climate change itself, and just drives a wedge between people who hold opposing views.

Meanwhile, if I’ve crafted the third example well enough, hopefully you can see that there is no evidence of ad hominem at all, and even though the poster is leaning toward one “side”, they have not shut down engagement.

Sieve Question Two

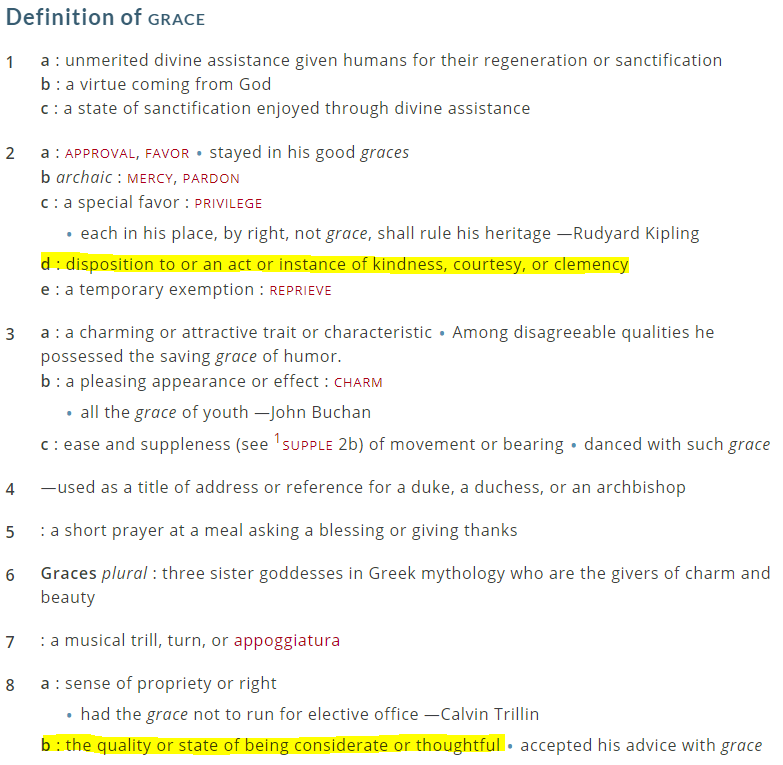

“Does my post allow for (and even maybe invite) respectful discourse with someone who disagrees with it?“

Fallacy This Helps Avoid: Straw Person

This occurs when, in refuting an argument or idea, you address only a weak or distorted version of it. It is characterized by the misrepresentation of an opponent’s position to make yours superior. The tactic involves attacking the weakest version of an argument while ignoring stronger ones.2

How to Tell

This is often used in conjunction with the ad hominem fallacy because it adds even more punch. After all, only moron would believe a weak argument. Most people have no desire to engage in discourse with someone who starts off with the premise that “Your position is weak, because it supports x so I am right and you are wrong and unless you can see that you are an idiot.” Consider the contentious example of abortion:

Example 1

“Pro-choice? So you think that murdering babies is ok!?! I guess you don’t care about the lives of the babies who get killed.”

Example 2

“Pro-life? So women should have no say over what happens to their own bodies?!? I guess you don’t care about the 13-year old girl who was brutally raped and is now forced to carry and give birth to the child of the man who scarred her forever.”

Example 3

“I struggle with the abortion issue. I believe it is a clear and terrible breach of fundamental human rights to tell someone else what they can or can’t do with their own bodies, regardless of the circumstances but especially when there is physical/psychological trauma involved that can be addressed with an abortion. But I am also really troubled by the fact that I am in no position to decide whether a viable fetus, at any stage of development, is a human life, and I don’t see how anyone could be, really. The issue feels like being offered only two choices where each choice is loaded with ethical downsides, and there is no option to not choose. I worry that in order to alleviate the moral weight of each choice, people downplay or even outright lie about the consequences of their position. So although I land on the side of pro-choice, I do not do so lightly, and I am aware that it feels like I have made a moral choice to prioritize the essential rights of the mother over the potential rights of the unborn child. I hope this choice is correct.”

Consider the first two examples. Will a pro-choice person who just got told they murder babies want to engage in anything other than hurling insults with this person? Will a pro-life person who just got told they don’t care about the effects of rape on a 13 year-old girl want to engage in anything other than hurling insults with this person? By attacking a weak/distorted version of the other side, each has set it up so that any engagement by someone with an opposing view will manifest as some level of support for the weak/distorted claim.

Meanwhile, in the third example, the author has ultimately stated a position. Would a pro-x person be open to understanding the author’s struggle? Would a pro-life person feel safe to engage in discourse? Does it seem that there is the possibility that anyone who engages – including the author – might change their minds about anything surrounding the issue, including about people themselves who hold the opposite position?

Sieve Question Three

“Does my post offer information/education that someone who disagrees with me might not have considered?“

Fallacy This Helps Avoid: Irrelevant Authority

This is committed when you accept, without proper support for an alleged authority, a person’s claim or proposition as true (and that alleged authority is often the person employing the fallacy). Alleged authorities should only be referenced when:

- the authority is reporting on their field of expertise,

- the authority is reporting on facts about which there is some agreement in their field, and

- you have reason to believe they can be trusted.

Alleged authorities can be individuals or groups. The attempt to appeal to the majority or the masses is a form of irrelevant authority. The attempt to appeal to an elite or select group is also a form of irrelevant authority.3

How to Tell

Are you claiming that some position is wrong? If so, have you explained how you know this? What authority are you citing? Or are you claiming expertise and asserting “Thinking x is wrong!”

Example 1

“Jordan Peterson says switching to a meat-only diet literally saved his life. Vegans are slowly killing themselves.”

Example 2

“I lost 30 pounds when I went vegan and feel so much better. Eating meat is asking for heart disease and dementia.”

Example 3

“It makes sense to at least consider evolution when determining what a ‘healthy’ diet looks like. Before humans had access to foods not native to our geography, the only people that would have survived would be the ones who thrived on what was available. So if your ancestors evolved in warmer climates, it would make sense that your constitution would welcome more grains and vegetables, whereas ancestors in colder climates would have evolved to thrive off meats.”

Consider the first two examples. Jordan Peterson is not an authority on nutrition (he actually takes great pains to make that clear whenever he talks about his diet). So while he has said that a carnivore diet works for him, it is not evidence that the carnivore diet is better than others. In the second example, the author is actually setting themselves as the authority. Neither example offers any warranted expertise or education and are strictly anecdotal claims.

In the third example the author poses an idea that promotes questioning and further research. They are not claiming any personal authority, or even choosing a side, even though they may have a preference. They are presenting an hypothesis that can be (and probably has been) analyzed by experts.

If you’d like to read more about informal fallacies often used in argument, I recommend this link from Texas State University. It lists the common ones and provides explanations and examples. One of my favourites is Begging the Question, which I always laugh about because it’s a phrase that gets used so often, and almost always incorrectly, while at the same time the real fallacy gets used regularly in arguments.

In any case, I hope we can all change the way we interact on social media and beyond. I really do believe we need that flavour of revolution.

Thanks for reading,

Rich