Anyone who voted for Trump is a white supremacist.

For many of you, reading that sparked a response charged with negative emotion. Some people probably got so angry they stopped reading and aren’t even here anymore.

Maybe you voted for Trump and took it as an attack. Maybe you hate Trump and got angry because you think the US has been overcome by white supremacists. Maybe you strongly agree with the statement. Maybe you vehemently disagree. There are lots of reactions that statement can instigate. But if it upset you, regardless of why, I offer my sincere apologies.

For the record, I disagree with the statement. In fact, I know it to be false. I’m Canadian, so I didn’t have a vote, but I have more than one personal acquaintance who did vote for Trump, and none of those people are white supremacists. That should be safe for me to say. Yet in many arenas, it isn’t. In many arenas, I would just have caused myself to be written off as a white supremacist too, among many other vile labels – guilt by association with a phantom assumption. And I haven’t even stated who would have gotten my vote if I had one which in any case is irrelevant. What is relevant though is how quickly and completely conversation gets shut down on critically important topics like this one that plague our collective discourse. This phenomenon demonstrates a fundamental lack of understanding, or perhaps worse, a deliberate lack of honouring, some core principles that we study in formal logic, which has roots both in philosophy and in mathematics.

Let’s switch to a less charged example.

Anyone who drinks water is a marathon runner.

It’s silly right? Drinking water does not imply that you run marathons, and to make the claim that it does is clearly ridiculous. What’s less absurd though would be saying that anyone who runs marathons drinks water. But even there, be careful, because there’s an association that many people will make that has nothing to do with why that sentence is true. See, although distance running does require proper hydration, that’s not the reason that marathon runners drink water. A marathon runner is a marathon runner even when they are not running. And they drink water for the same reason non-marathon runners drink water. In fact marathon runners drink water for the same reason all humans, not to mention marine mammals, sea birds and even trees drink water. Because they need it to survive. So if you discover someone drinking water, it’s not likely you would jump to the conclusion that they are a marathon runner. The distinction between “If you are a marathon runner then you drink water” and “If you drink water then you are a marathon runner” highlights the difference between what formal logic calls implications and their converse. It’s important to understand this concept, so let’s work on a short lesson.

First, we need to understand what we mean in formal logic by a statement.

Definition of “Statement“

In formal logic, a statement is a sentence that has a definite state of true or false. Some examples:

“Justin Timberlake is older than Justin Bieber.”

(provably TRUE statement)

“5 is an even number.”

(provably FALSE statement)

“‘5 is an even number’ is a statement.”

(humorously constructed TRUE statement)

“There is sentient life on other planets.”

(Definitely either TRUE or FALSE, but although I have a guess, I have no proof that I’m right)

We can not always tell if a statement is true.

Although it’s fairly easy to tell if a sentence is a statement, it’s often difficult or even impossible to tell if it’s true or if it’s false. The statement “There is sentient life on other planets” does have a definite truth value, though we can only guess at what that value might be. And that’s where opinion enters the arena. Now consider this much more highly charged statement: “An unborn fetus is not a living human.” I bet that one sparked some intense emotion in many readers. And I’d also be willing to bet that the emotion it sparked is tied to your opinion about whether or not it is true.

That’s just your opinion

Guessing at the truth value of a statement is my preferred way to define opinion. We can argue over what we think about aliens from other worlds, or when human life begins, but until we have evidence that proves or disproves our position, all we are doing is voicing opinion. Isaac Newton said it well:

(We) may imagine things that are false, but (we) can only understand things that are true, for if the things be false, the apprehension of them is not understanding.

Isaac Newton

So we can apprehend (consider in our thoughts) beliefs and opinions, but false is false, so any belief attached to a false thing is not true understanding. Compounding the problem this highlights is that it is human nature that purging a disproven belief requires a deliberate and often painful reorientation, so often what we see is denial, and a loyalty to a false opinion. It might be human nature, but it’s dangerous.

Consider this thought experiment:

Suppose you are pro-choice, because you indisputably support the right of a human to make decisions about their own body. It would likely (but admittedly not certainly) then be the case that you also believe that the fetus is not a human, and so there is no conflict between the rights of the mother and the rights of another human. Then suppose you learned, conclusively, that a fetus is a human baby, effectively equating abortion with homicide. How would that make you feel? Would it be easy to change your position? In this thought experiment, where the premise is that it has been proven that a fetus is a baby, would you choose to deny that truth?

It’s an extremely difficult thing to think about dispassionately. But beware when asserting opinions as facts, and be prepared to understand that until a fact is known/proven, your opinion will differ from that of others, and arguing with them without establishing that both arguments are predicated on opinion is more of an exercise in charisma than debate.

Opinion Vanishes in the Face of Proof

Once the truth value of a statement is established via proof, opinions are rendered irrelevant, and they only persist as the result of deliberate obstinacy, miseducation/delusion, or in many cases, indoctrination. Interestingly, this applies even if your opinion happens to align with the truth. If it is your opinion that there is sentient life on other planets because you believe Star Trek is a documentary, then even if there is sentient life on other planets your opinion is based on delusion, and the fact that you are correct is coincidental. Think of it this way: If you’ve been maintaining that there is life on other planets because Captain Kirk fought a Gorn, and one day life is discovered on another planet, you would look pretty foolish proclaiming that you were right all along. So whether “correct” or not, opinions are just opinions. It is interesting to consider the ramifications of using miseducation to deliberately delude uneducated people into having an opinion that aligns with the truth, but maybe that’s a topic for a different article.

Ok, so hopefully we understand now that a statement is either true or false, and that we can’t always know which it is. Furthermore, if we guess, then we are forming opinions. This gets even more interesting (if that is the word for it) when we create compound statements by linking statements conditionally. Like saying “If you voted for Trump then you are a Nazi.” Using If/then to link statements is called implication. We use them a lot.

Definition of “Implication“

“If you are reading this article, then you understand English.”

Is that true? I think so. In any case, that statement is an example of an implication – a compound statement that conditionally links two statements. Implications claim that if we know that one statement (called the predicate) is true, then we can conclude that a second statement (called the conclusion) is also true. Even though implications don’t always present the same way, they can always be formulated using “if/then”.

Because implications are statements, they will either be true or false. For example:

Predicate: I was born before 1970

Conclusion: I am older than 30

“If I was born before 1970 then I am older than 30”

True – based on arithmetic

Predicate: A person is wearing pants

Conclusion: That person is hungry

“If a person is wearing pants, then that person is hungry”

False – a person who was wearing pants and was hungry, who has just eaten their fill, will still be wearing pants (though they may have unbuttoned them!)

Any statement that can take the form “If A, then B“, which is to say “A implies B“, is an implication. For example:

“All football players use steroids”

can be reformulated as

“If you are a football player then you use steroids.”

It is worth noting that the above statement about football players is an example of a false implication, even though it is the opinion of many. Unlike opinion, truth is not ascertained or even swayed by consensus.

It’s also important to distinguish between the truth of an implication, and the truth of the conclusion. For example, “If I win a hundred million dollars in the lottery then I will buy a Lear Jet.” is a true implication (ask my wife – we’ve discussed it), but it does not mean I am going to be buying a Lear Jet. When “A implies B” is true, it doesn’t mean B is true, or even that B could ever be true. It just means that if you observe that A is true, then you can conclude that B is also true. This connection actually has a cool Latin name in formal logic. It’s called Modus Ponens.

Modus Ponens

Modus Ponens is a special implication that we use to make deductions by citing established implications. It says “If A implies B, and A is true, then B must also be true.” A very common error is when people pervert modus ponens into “If A implies B, and B is true, then A must be true.” This is faulty. Consider this example:

“If you stick your hand into a toaster while it’s on, you will burn your hand.”

This is true.

Now consider these two arguments:

Modus Ponens

“I see you stuck your hand into a toaster while it was on. You must have burned your hand.”

Faulty Deduction (perverted Modus Ponens)

“I see you burned your hand. You must have stuck it into a toaster that was on.”

This perversion of modus ponens can also be dangerous. Imagine the implication “If you are racist then you supported Trump” is true. Now consider this faulty deduction: “I see you supported Trump. You must be a racist.” This is precisely the sort of perverted logic that divides and fragments society, potentially irreparably.

This leads us to the notion of the converse of an implication, and the contrapositive.

“Converse” and “Contrapositive”

Every implication has a converse and a contrapositive. The converse switches the predicate and the conclusion, so the converse of “A implies B” is “B implies A“. On the other hand, the contrapositive of “A implies B” is “not B implies not A“. The contrapositive means that if you know the conclusion is false, then you can conclude that the predicate is false. It’s essentially saying the same thing as the implication, in a different way. That argument has another cool Latin name: Modus Tollens:

Modus Tollens

Like Modus Ponens, Modus Tollens is used to make deductions using established implications. It says “If A implies B, and B is not true, then A must also not be true.”

Consider this example, which demonstrates the ideas of implication, contrapositive, and converse. Suppose you took a Spanish course where students who fail earn a grade of F:

Implication:

“If I got a C, then I passed the course.”

(True – A credit is awarded for any grade other than F)

Modus Ponens: ” I see that you got a C, so you must have passed the course”

Contrapositive:

“If I didn’t pass the course, then I didn’t get a C.”

(True – not passing – i.e., failing the course, means you got an F)

Modus Tollens: “I see that you failed the course, so there’s no way you got a C.”

Converse:

“If I passed the course, then I got a C.”

(False – You may have gotten an A, B, C or D.)

Faulty logic: “I see you passed the course, so you must have gotten a C.”

Notice that the implication is true, the contrapositive is also true, but the converse is false.

Sometimes the converse is true, and sometimes it is false

For true implications sometimes the converse is true:

“If we have a common biological parent then we are biological siblings.”

has the converse

“If we are biological siblings then we have a common biological parent.”

and sometimes it isn’t:

“If our fathers are brothers then we are cousins.”

has the converse

“If we are cousins then our fathers are brothers.”

So knowing an implication is true does absolutely nothing to tell you if the converse is true – or false. Yet there is a strange insistence in public discourse that true implications always have true converses. This is glaringly demonstrated in political discourse.

How would anti-immigration voters have voted?

Consider this implication, which may or may not be true (probably is), but many readers will definitely have an opinion about it:

“If you are racist then you will not hire a black candidate.”

Now consider the converse:

“If you did not hire a black candidate then you are racist.”

I have heard this claimed countless times. And there’s no logical foundation for it. This highlights another common error people make. Implications create links (being racist links to not hiring black people), and people then use those links to try and reverse-engineer a converse (not hiring a black person links to being racist). This can be attributed to the notion of ruling out. Suppose that all immigrant-haters voted for Trump, and that you did not vote for Trump. Then using Modus Tollens I can rule you out as an immigrant-hater (you did not vote for Trump, so you must not hate immigrants).

However if you did vote for Trump, then I can’t use Modus Tollens or Modus Ponens to disprove (rule out) the possibility that you hate immigrants, because in the implication we are citing, hating immigrants is the predicate, not the conclusion, and all I have observed is the conclusion. So your position on immigrants is something I’d have to look at other factors to determine.

Not being able to disprove a statement does not mean it’s true

True: “If you get a D in Spanish, then you earn a credit.”

Suppose you believe that I got a D in Spanish. Now suppose that in an attempt to prove that you are correct, you do some digging into the school records and discover that I did take Spanish, and that I earned a credit. Does that mean I got a D? You can’t tell. All you know for certain is that I am in the group of people who earned a credit. You hopefully also know that anyone who earned an A is in that group. Me being in the same group of people who earned a D is not proof that I earned a D, because all the credit-earners are in that group, and they did not all earn D’s. You could say that you have gathered some evidence that I earned a D, but you can not say that you have proven it. So you have neither proven nor disproven your belief. On the other hand, if your digging showed that I took the course but did not earn the credit, Modus Tollens rules out the possibility that I got a D, and your opinion is false. Which is to say, “You did not earn a credit, therefore you did not get a D”.

So then if it’s true to say that immigrant-haters voted for Trump, and you know your coworker voted for Trump, then all you know is that your coworker is in the same group as immigrant-haters. Now even though you can’t rule it out, you can not conclude that your coworker hates immigrants. So if you start a conversation with them by accusing them of hating immigrants, that’s bound to go poorly.

Implication does not imply causation

We also need to think about a common misconception, which is that true implications are therefore causations. That’s the false belief that if we know that “A implies B” is true, it must mean that “A causes B”. This is actually just another example of mistakenly believing a converse:

“If A causes B then A implies B” is an implication where the conclusion is also an implication, and it’s true.

The converse, “If A implies B then A causes B” is false.

Consider this example, which has embedded causation:

Let A be the statement “Your car has no fuel” and

Let B be the statement “Your car won’t start.”

So:

not A is the statement “Your car has fuel” and

not B is the statement “Your car will start.”

Implication (If A then B):

“If your car has no fuel then it won’t start.”

(True – Cars with no fuel won’t start, and even if there are other things wrong with the car that we don’t know about, knowing it has no fuel allows us to invoke causation to conclude it won’t start)

Contrapositive (If not B then not A):

“If your car will start then it has fuel.”

(True – You can’t start a car if it has no fuel)

Converse (If B then A):

“If your car won’t start then it has no fuel.”

(False – there are lots of reasons why a car won’t start and being out of fuel is only one of them)

… which brings me to strength-training.

What Does This Have To Do With Strength Training?

The car example shows that even when causation is the reason an implication is true, we still don’t get the converse. But sometimes the example in question is less clear, and people jump to conclusions.

For example:

Truth Due to Causation:

“If I participate in a strength-training regimen at the gym, then I will get stronger”

(True because of the causal relationship between strength-training and getting stronger)

So we have an implication that is true because of causation. The converse is “If I got stronger, then I participated in strength-training at the gym”. That’s a conclusion people jump to all the time. “Oh, you have gotten stronger – you must have been working out!” False. Lifting weights in the gym is not the only way to get stronger. Someone who gets a job that requires heavy lifting will also get stronger. Children get stronger just by growing. So if you find someone who has “gotten stronger” you cannot automatically conclude that they started a strength-training program at the gym. Again, even when there is causation, a true implication is not proof that we have a true converse.

It’s time to bring this back to public discourse. It’s crazy-making to see how many people seem to think that the converse is always true. Or if not, they pretend they do, to fool others into buying an argument. Let’s look at an extremely charged example: rape.

All rapists are men

This isn’t technically true, but while a very small percentage of rapes are not perpetrated by men, the vast majority are. This is a horrible truth. One that has troubled me since I was old enough to have learned it. As a thought experiment, let’s simplify this and for a moment assume that all rapes are committed by men. So then we would have this implication:

“If you are a rapist, then you are male.”

But consider the converse:

“If you are male, then you are a rapist.”

I hope we can clearly see that the converse is false. Sadly, I have heard this converse claimed (or implied) many times, and it does nothing at all to help the real issue of rape. Good people want to eradicate rape, because rape is monstrous, and good people want to reduce suffering. Taking good men and lumping them in with bad ones by claiming masculinity as the driving force behind the desire to rape, creates extra suffering. It makes no sense.

There are many other places where we see the converse invoked dangerously. One chilling example is when someone asserts that an implication is true, but then get accused of having supported the converse. This then changes the conversation about a potentially difficult issue into one of accusation and defense.

I will list some examples of implications I have heard claimed, where an immediate switch to the converse then changes conversation to the wrong topic. As an exercise, in each case, state the converse of the implication in your mind and ask yourself what trouble that might cause, and how it would poison the (potentially difficult) conversation. As I said, these are heavily charged statements. In many, if not all cases, the reason they are heavily charged is probably not the implication, but what the converse would mean, if it were true.

I feel that I have to repeat that I am not claiming the implications in the examples are true, though I know they are the opinion of many. But if they are true, it’s because they are, and if they are not, it’s because they are not. Opinion vanishes in the face of knowledge. Still, arguing about the converse has nothing to do with either of those cases and changes the dialogue into something irrelevant. It’s important, as you read, to keep the dispassion of viewing claims through the lens of formal logic. For each implication, consider what it would mean if it were true, and whether the converse would then also apply.

Do you think any of these are true?

Do you think their converse is true?

- If a person is a white supremacist, then that person would have supported Trump over Harris.

- If a person is a mass killer, then that person is a gun owner.

- If a person is a member of Hamas, then that person is Muslim.

- If a person is misogynist, then that person is male.

- If a person is a stalker, then they will like all your photos on Instagram.

- If someone wants to rob you, then they will walk behind you at night.

Do you think any of these are true? If so, do you also think the converse is true? If you think the converse is true, is your evidence of this that the original claim is true? If so, you have no foundation to back the claim to the converse. Seriously. None. Hopefully this article has made that clear.

Just because an implication is true, it does not mean its converse is also true.

And yet there seem to be a huge number of people out there who think that it is impossible to hold to a claim and not hold to the converse. For example they think that if you talk about mass killers being gun owners then you want to paint all gun owners as mass killers – which is a ridiculous notion on so many levels, perhaps the most obvious being the staggering number of gun owners who are not killing anyone with them – and they label you as ignorant, or as a fear-mongering anti-freedom fanatic with a hidden agenda. But there is simply no logical foundation for this connection. What they are doing, from a logical perspective, is saying that since you believe an implication is true, you also believe the converse, and so you are pushing a hidden agenda. And I just can’t say how many ways this is wrong, and dangerous.

“But wait!” some say, “fear-mongering anti-freedom fanatics pushing a hidden agenda DO say that most mass killers are gun owners! So by saying that aren’t you one of them?”

Once again, they are invoking the converse of an implication, possibly without realizing it – though I suspect in some cases fully realizing it and doing so anyway to redirect away from rational discourse. “If you have a hidden agenda then you will say that most mass killers are gun owners” is not the same as “If you say that most mass killers are gun owners then you have a hidden agenda”.

To illustrate just how silly all of this is, I’ll talk a little about probability, using Venn Diagrams. This time we’ll talk about serial killers.

Most Serial Killers Eat Breakfast

This is an implication, but what’s not immediately obvious is that it invokes a probability statement due to the word “most”. It means that if you encounter a serial killer, then they probably eat breakfast.

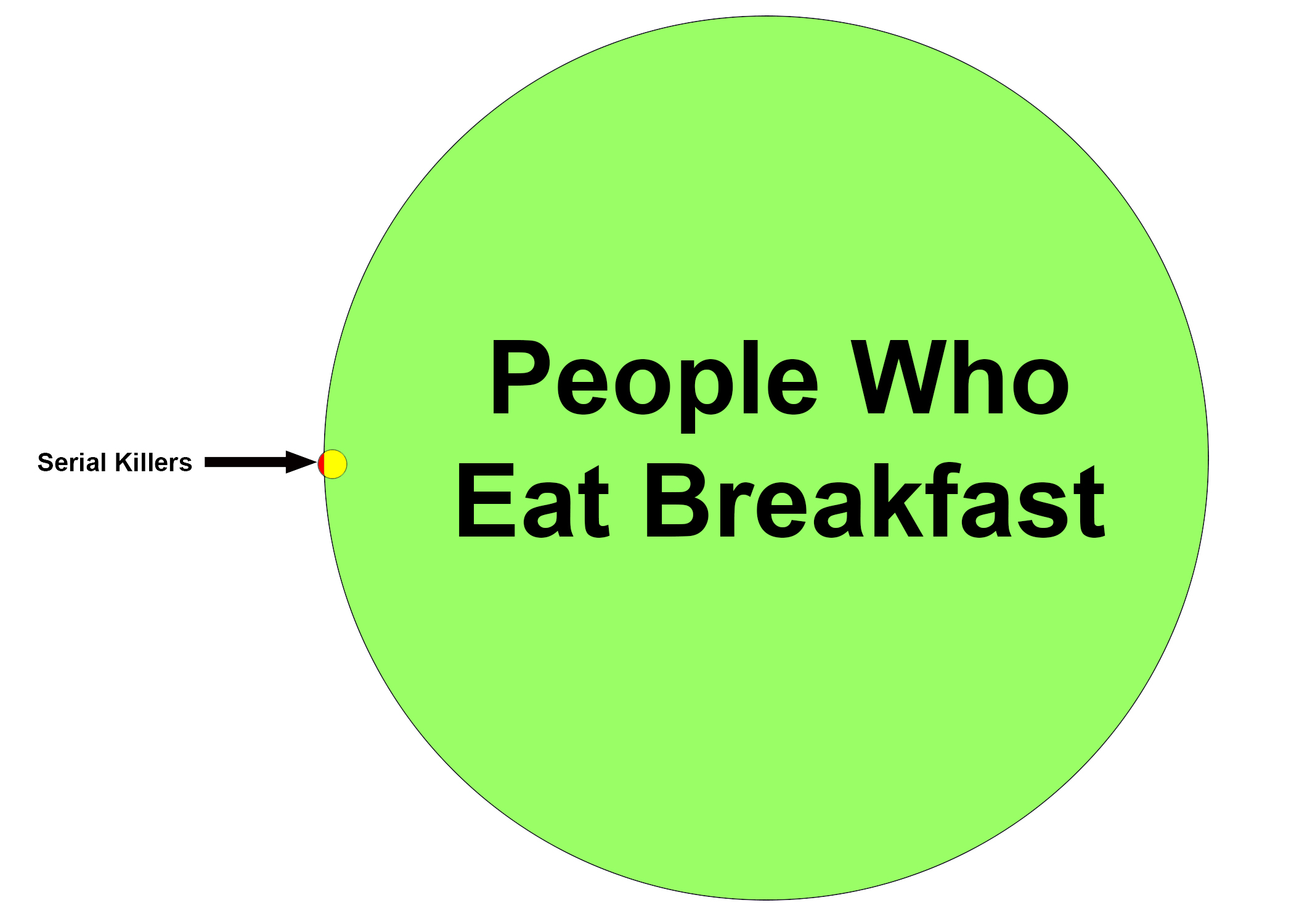

Because of how we use the word most, it arguably means anywhere between 50% and 100%, so for the sake of argument, let’s suppose that 80% of serial killers eat breakfast. I’m sure that number is low, but I’m thinking that if I attempt to consult studies on the eating habits of sociopathic murderers, I may find limited data has been collected. In any case, assuming 80%, a visual representation might look like this:

So if you want to bet on whether a particular serial killer eats breakfast, and you don’t know ahead of time, you should make the bet, because you will probably win.

Now consider this Venn Diagram:

Even though the green circle isn’t nearly large enough (if it were, we wouldn’t even see the yellow part), this still demonstrates that most people who eat breakfast are not serial killers. Think about how much green there is compared to how much yellow. So if you came upon someone eating breakfast, you should be pretty confident that they are not a serial killer, keeping in mind that it doesn’t constitute proof that they are or that they are not. I’m thinking that is probably the case for you – that you don’t consider breakfast-eating to be compelling evidence of evil.

Being in the same group as someone does not mean you share all the same qualities

When someone says or does something that a serial killer, (or a racist, a rapist, a transphobe, a misogynist …) might do, it is false and dangerous to conclude that that person is one of those evil things. Notice the italics on the word might. That’s a probability word. A rapist might have eaten breakfast today. So might a non-rapist. And there are way more of those. To call someone a rapist, you would hopefully be using evidence they had raped someone, not evidence that they had eaten breakfast.

Or evidence that they are male.

Bad People Can Say True Things

It’s true. Truth is not the sole domain of the virtuous. Truth, in fact, like justice (purportedly) is blind. And it’s critical that we do not devalue the truth of a statement just because it aligns with the opinion of someone nefarious.

For example, someone who hates Muslims would be willing to assert that most suicide bombers have been Muslim, because it would further their agenda of hate, especially for those who immediately jump on the converse, which is clearly absurd. But if the claim is true, then a rational thinking non-racist could also say it. To then say “well islamaphobes say that, therefore you are islamaphobic” is to claim a converse that isn’t true. What’s far worse is that the label shuts down conversation. And if we can’t talk about things that are problematic, like racism, mass shootings, terrorism, sexual assault, or a myriad of other difficulties we face in modern society, how can we make things better? We can’t.

Good People Should Say True Things

Especially when it is hard, and even if it coincidentally aligns with the opinions of assholes, it is critical to acknowledge true things as true. Good people want to reduce misery in the world. Good people want to increase happiness in the world. Please don’t use the trick of claiming the converse to stand in their way. Let’s allow honest discussion to flow.

Thanks for reading,

Rich