Wow. An alliterative title that I didn’t even plan. I feel so clever. Which is ironic…

I’m 55 years old. By all accounts an adult. 55 is to human age as medium-well is to steak doneness, so I guess I’m the right side of middle-aged. Yet it seems nobody has informed my psyche. The child never left, and I don’t imagine it ever will – nor do I want it to. The only thing I can claim as I’ve aged is that I recognize the child in me, and I have no desire to evict that element of my psychological makeup. I simply want to work to understand its complexities and nuances, and see when my behaviour is more strongly guided by its influence. One aspect of this, and perhaps the only aspect that matters, if you dig deep enough, is the lasting effects of what I call Parental Promotion.

I have come to realize more and more clearly that my path in life has been strongly guided by what I think of as my parents’ promotional campaign, specifically about me. My parents, my mother primarily, never missed an opportunity to tell me and anyone who would listen that I was amazing. For example, according to my mother I was, among many other things:

- The smartest kid.

- A true mensch (this is a Yiddish word that essentially means a decent person).

- The most talented singer. This is minor but illustrative, as I will discuss shortly.

They were also able to find ways to go on about my amazing “deficiencies” too, as though they were miraculous. I was, for example, among many other things:

- The most intensely shy kid anyone ever met.

- Exquisitely careful. I would come home from a day of playing outside with my friends and my clothes would be as clean as when they came out of the dryer.

- Deeply quiet. While other kids would be talking, shouting and making noise, I’d be silently observing.

I believed all of it. Not “believed” as in they had to convince me away from a different opinion. Believed at my very core, without even the thought of questioning. I took it all as generally accepted fact. I was the smartest. I was the best singer. I was intensely shy. To be explicitly clear here, I’m not listing these as my own evaluations. They were not observations I made about myself. I didn’t decide these were true based on judgment or comparison. I am saying that because my parents told me they were true it meant they were axiomatic, and thus everyone would know it. It was my childlike perspective that if a fact is a fact then it must be universally known. Like the sky being blue. You don’t have to talk about it – it’s given. You assume everyone knows it. And if it comes up in any context, you don’t consider that it might be contentious or a matter of opinion because, well, look at the sky. It’s blue. Certainly, you don’t stop to consider how it will make you look to others when you act like it’s true.

From my earliest memories, and stretching even until today, this had objectively interesting effects on my interactions with people. Here are just a few (possibly obvious) results.

One, believing I was great (again, I stress, this was not a judgment of myself but taken as fact since it was what my parents told me), and believing that everyone knew this, and also believing that I was quiet and shy and that everyone knew that, I was most commonly seen by others to be snobby and aloof. As I aged this morphed into snobby, aloof and intimidating. Because none of these are internally true about me, and not remotely what motivated my behaviours, I was constantly taken by surprise by people’s reactions to me, which were consistent with their perception of me but so totally dissonant with my inner thoughts and motivations. I really never understood how I could be so misunderstood.

One immediate and persistent impact this had was to make me even more quiet and withdrawn, socially. That may have amplified some incorrect assumptions, but at least it didn’t create openings for discordant reactions to me, which I never learned how to reconcile.

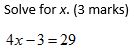

To this point, I grant that I’ve certainly painted an unpleasant picture of the effects of my parents promotional campaign. But it’s not as simple as that. For example, believing that I was smart, I just assumed I could always figure something out. That if I was confused, or frustrated, then it was temporary and just meant I wasn’t thinking hard enough, or more likely was approaching a problem from the wrong direction. This attitude is self-fulfilling. It’s not news to anyone that confidence is a key – maybe even the most important – ingredient to success. Taking your innate ability as axiomatically true is a clear manifestation of confidence. It has led me to success professionally as a math teacher, and in many side pursuits such as visual arts, weightlifting, and sometimes, writing.

That’s not ego, although it can be perceived that way. I am reminded of a Bruce Lee quote: “If I tell you I’m good, probably you will say I’m boasting. But if I tell you I’m not good, you’ll know I’m lying.”

In any event, what I mean is that it’s just an understanding of your own capability and what that means you can do. For my whole life, to this very moment, I have always believed that I can excel at something if I want to. And often, but not always, I prove myself right. I no longer believe this is simply how I was born though. Now I recognize that my parents made me believe it was, and that is enough. When I don’t succeed, I have also realized that my confusion about that was a result of it being in conflict with the notion that it could never happen. I will illustrate with an example that often comes to my mind often. It was the first time I auditioned for a part in a musical.

For background, I was about 40 years old. I hadn’t been on a stage since school plays. Through a friend I discovered a local theatre program that put on amateur musical productions. The way it worked was you paid a fee for the program, and anyone could join. It was a way for adults to experience the fun of performing in musical theatre. Rehearsals happened once a week, and for the first two rehearsals parts were not yet assigned, although you can bet that everyone was assessing everyone else, and how they stacked up against the others, and people were making it clear which parts they were aiming for. The third rehearsal was auditions, and everyone would audition in front of everyone else. The director would let you sing whatever song from the show that you wanted to sing, and then usually ask you to sing and perform a few other numbers. Later that week he would send out the casting, and from then on the rehearsals were more focused. The experience culminated in two performances that were always well attended by family and friends. It was a lot of fun. I did many plays with this company, but that first one was Les Misérables.

After the first two rehearsals, it was clear (to me) that I was one of the best males in the room. It is clear to me now that I was not. But even at 40, that belief that I was great still guided much of my self-evaluation. I was hoping that I would get the part of Javert. And after the audition, I felt sure that I would. There were other cast members who told me they thought I had done well, and the feedback I was getting after each of my songs seemed to confirm that too. What I wasn’t able to filter though, was that people in that environment, wanting to be nice and supportive, compliment everything. Which incidentally is something I have learned not to do, because then the genuine, deserved compliments get lost in the sea of politeness, but that’s another story.

The point of this example is to tell you that I did not get cast as Javert, or any male lead. I was cast as sailor #3, prisoner #1, policeman #2, and a few other similar roles. I wasn’t devastated when we got the casting. I was confused. I also never resented any of the other cast members, because why would I? They didn’t make any mistakes, the director did, although because my parents emphasized being a mensch, I wasn’t angry with him, only grateful for the process he had created. However throughout the rest of the rehearsals, and for a very long time afterwards, I wondered what went wrong. And I started to realize this was a manifestation of the long-term impact of my parents’ promotional campaign. Eventually, after many, many more shows, I developed a more realistic understanding of my abilities as a singer. I am decent. That’s it. No more, no less. Nobody is going to think I have a great voice, but they won’t complain about it either, and that’s fine. But it took a while to see through the filter of the lens of my parents’ praise.

If I can simplify a very complicated concept, what I’ve learned is that believing what my parents told me has been at times a good thing, and at other times a difficult thing. It has led me to excel in many ways, and also led me to confusion and hurt when it conflicted with a more austere reality. But truly, the lasting gift is that at my core, I always believe I’m worthy.

It has been said, by people wiser than me, that the way we talk to our children becomes their inner voice (a quick google search tells me that this sentence may have originated with Becky Mansfield). My parents’ campaign became my inner voice, and my inner voice is kind. That’s powerful. It has brought me great things, and hard things. In my case, it’s been a net good, and I am grateful for it. But I have seen the results of more destructive campaigns on many of my adult friends, and on many of my students (as I alluded to above, I am a high school teacher and tutor). So my final message is this:

To children (and that means all of us). Reflect on how your parents’ campaign has guided your path. Try to see it clearly. Tease out the good it has brought, and work to understand the bad. The process is very healing.

To parents. Think deeply about your campaign. Remember that your children do not have the context of a lived life to apply to what you tell them about themselves. They may believe high praise, or they may wonder why what seems ordinary to them is generating high praise. They will believe harsh criticism. Tearing them down does not “build character”. It builds a cruel inner voice that it will take them years (if ever) to understand is not their own, and does not speak truth.

Campaign honestly. Campaign proudly. Campaign positively.

Thanks for reading,

Rich

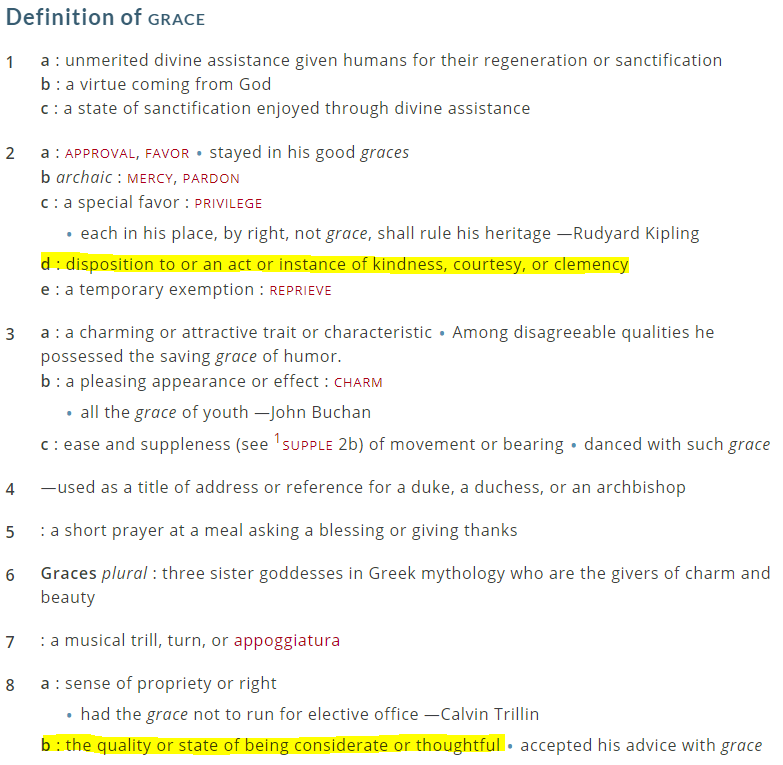

Starting around the age of 8 or 9, and lasting for 3-4 years, it starts to become obvious which of the girls are well suited to dance and which are not. This obviousness is not lost on the girls. Dance becomes a micro-society where “Haves” and “Have-Nots” start to identify, and the behaviours that result are what you would expect. In a way it mirrors what is happening at that age in school, but from where I sat it was definitely magnified at dance. These can be pretty difficult years for the girls, and perhaps more so for the parents. As I watched from the sidelines, I always told myself that whether a Have or a Have-Not, there are very valuable lessons to be learned from these dramas, and whether my daughter was receiving or giving grief (it certainly seemed she was receiving a lot more than giving, but nobody ever accused a dad of being impartial), my wife and I always did our best to ground her in reality and look for the long-term life lessons that could be taken. I do think, subjectivity aside, that I can safely say my daughter began to show real talent for dance during this time. I can also say, objectively this time, that she emerged from this phase with an inner-strength and confidence that is astounding. As I watch her navigate the social quagmire of the tenth grade, I am exceedingly proud and awed at how well she manages to stay true to herself and her friends, while gliding above the drama that can consume most kids of that age. She never judges others, and always stays honest in helping her friends deal with whatever the current issue is. In and out of the dance world I have watched her handle victories with honest grace and compassion, and failures with resolute determination. She’s my hero, and I firmly believe we have the “emerging talent” years of the competitive dance program to thank for that.

Starting around the age of 8 or 9, and lasting for 3-4 years, it starts to become obvious which of the girls are well suited to dance and which are not. This obviousness is not lost on the girls. Dance becomes a micro-society where “Haves” and “Have-Nots” start to identify, and the behaviours that result are what you would expect. In a way it mirrors what is happening at that age in school, but from where I sat it was definitely magnified at dance. These can be pretty difficult years for the girls, and perhaps more so for the parents. As I watched from the sidelines, I always told myself that whether a Have or a Have-Not, there are very valuable lessons to be learned from these dramas, and whether my daughter was receiving or giving grief (it certainly seemed she was receiving a lot more than giving, but nobody ever accused a dad of being impartial), my wife and I always did our best to ground her in reality and look for the long-term life lessons that could be taken. I do think, subjectivity aside, that I can safely say my daughter began to show real talent for dance during this time. I can also say, objectively this time, that she emerged from this phase with an inner-strength and confidence that is astounding. As I watch her navigate the social quagmire of the tenth grade, I am exceedingly proud and awed at how well she manages to stay true to herself and her friends, while gliding above the drama that can consume most kids of that age. She never judges others, and always stays honest in helping her friends deal with whatever the current issue is. In and out of the dance world I have watched her handle victories with honest grace and compassion, and failures with resolute determination. She’s my hero, and I firmly believe we have the “emerging talent” years of the competitive dance program to thank for that. watching So You Think You Can Dance since season 2. It’s a great show to be sure, but I admit at first I was too absorbed in marveling at the physicality of it to understand what it communicates, despite the fact that the judges on the show really do a great job emphasizing this (I always assumed they were saying it metaphorically). But like a child that learns to speak simply from hearing the spoken word and contextually absorbing meaning from the sound, I began to absorb meaning from the movement. The first thing I realized was that unlike languages that use words, dance doesn’t translate to any other language, and communicates things which can’t be communicated any other way, with the possible exceptions of fine art, or poetry. Really good fine art will enthrall and speak to the viewer through infinite contemplation of something static. Really good poetry succeeds at using words which individually can be quite linear, by combining them in a way to create depth and consequently say something the language the poem is written in was not necessarily designed to say. Really good dance? A different thing entirely. It speaks to our humanity on multiple levels, and the fluidity of it allows the choreographer/dancer to tell us stories no written word could approach.

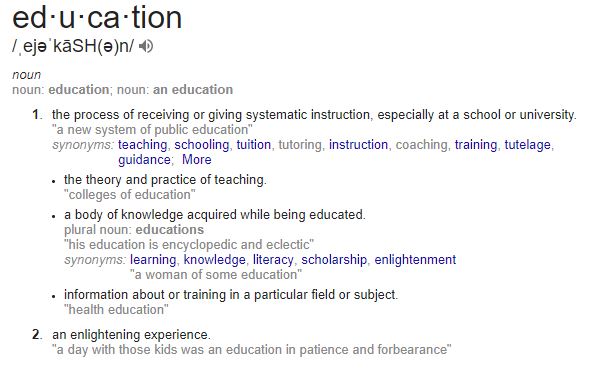

watching So You Think You Can Dance since season 2. It’s a great show to be sure, but I admit at first I was too absorbed in marveling at the physicality of it to understand what it communicates, despite the fact that the judges on the show really do a great job emphasizing this (I always assumed they were saying it metaphorically). But like a child that learns to speak simply from hearing the spoken word and contextually absorbing meaning from the sound, I began to absorb meaning from the movement. The first thing I realized was that unlike languages that use words, dance doesn’t translate to any other language, and communicates things which can’t be communicated any other way, with the possible exceptions of fine art, or poetry. Really good fine art will enthrall and speak to the viewer through infinite contemplation of something static. Really good poetry succeeds at using words which individually can be quite linear, by combining them in a way to create depth and consequently say something the language the poem is written in was not necessarily designed to say. Really good dance? A different thing entirely. It speaks to our humanity on multiple levels, and the fluidity of it allows the choreographer/dancer to tell us stories no written word could approach. remember once at a dance recital there was a senior acro small group number about to start (see what I did there – Dance Dad knows the terminology). It was clear from the opening positions that one of the dancers was going to execute a crazy trick to start the dance. Before the music started there were hoots and hollers from the wings and from the audience, and one dancer’s voice from the wings rang out with “You GO girl!”. I was momentarily taken aback. I think maybe I had just read an article or watched a show where that phrase was called into question as demeaning to women. And then I looked around. The stage and venue was dense with strong, confident young women, certain of themselves and certain of their power. And the dancer who called it out numbered among them. I couldn’t see anything demeaning at that point about what she had said, but on a deeper level I realized just what dance had done for these kids. It showed them what inner strength, determination and dedication could do. And so naturally I began to think about the dancers I’ve taught in my math classroom and I had this moment of revelation. It is exactly that quality that has always made them stand out to me in that setting. Not that they all excel in math, because not all kids do. But that regardless of their abilities in math, there is always an inner strength and peace that says “I know who I am, I know what I can do, and I know how to commit to improving.” Where many students in high school still need the explicit motivation that our culture seems to thrive on too often, the dancers have internalized their motivation in the best way. I can’t say enough how important that is for success in life.

remember once at a dance recital there was a senior acro small group number about to start (see what I did there – Dance Dad knows the terminology). It was clear from the opening positions that one of the dancers was going to execute a crazy trick to start the dance. Before the music started there were hoots and hollers from the wings and from the audience, and one dancer’s voice from the wings rang out with “You GO girl!”. I was momentarily taken aback. I think maybe I had just read an article or watched a show where that phrase was called into question as demeaning to women. And then I looked around. The stage and venue was dense with strong, confident young women, certain of themselves and certain of their power. And the dancer who called it out numbered among them. I couldn’t see anything demeaning at that point about what she had said, but on a deeper level I realized just what dance had done for these kids. It showed them what inner strength, determination and dedication could do. And so naturally I began to think about the dancers I’ve taught in my math classroom and I had this moment of revelation. It is exactly that quality that has always made them stand out to me in that setting. Not that they all excel in math, because not all kids do. But that regardless of their abilities in math, there is always an inner strength and peace that says “I know who I am, I know what I can do, and I know how to commit to improving.” Where many students in high school still need the explicit motivation that our culture seems to thrive on too often, the dancers have internalized their motivation in the best way. I can’t say enough how important that is for success in life.